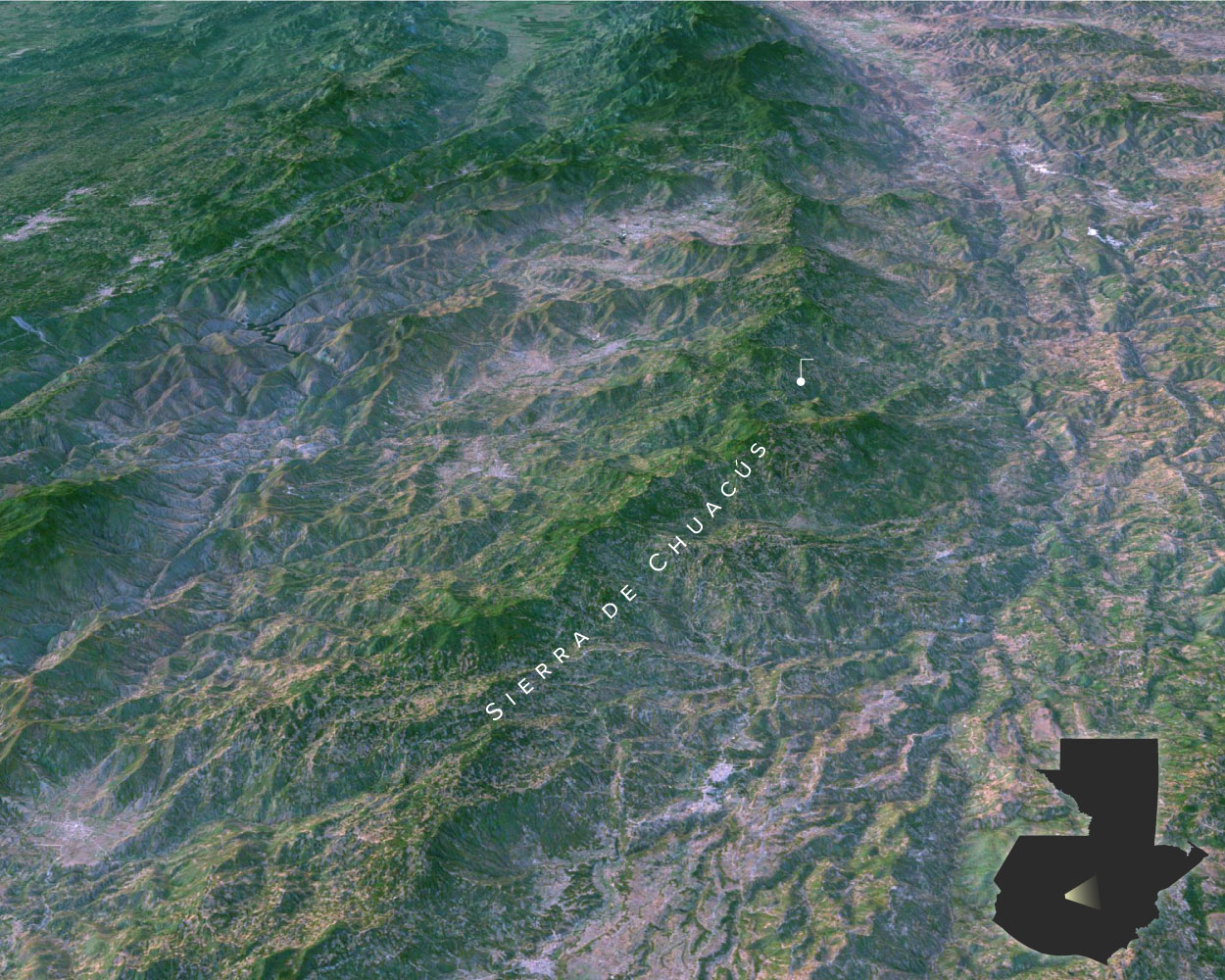

Claudia Patricia Gómez González grew up in La Unión Los Mendoza, a small town nestled in the western highlands of Guatemala, ancestral territory of the Maya Mam people.

On May 7th, 2018, she left the home she had known all her life.

Photo: Fabio Erdos/ActionAid

Felipe

Jakelin

Chuj

90,000+

Q’eqchi’

1.3 million+

Mam

840,000+

Achi

160,000+

Claudia

Juan

Carlos

Ch’orti’

110,000+

Wilmer

Felipe

Jakelin

Chuj

90,000+

Q’eqchi’

1.3 million+

Mam

840,000+

Achi

160,000+

Claudia

Juan

Ch’orti’

110,000+

Carlos

Wilmer

Felipe

Jakelin

Chuj

90,000+

Q’eqchi’

1.3 million+

Mam

840,000

Achi

160,000+

Claudia

Juan

Carlos

Ch’orti’

110,000+

Wilmer

itza’

Mopan

Chuj

Garifuna

Q’anjob’al

Popti

Akateka

Q’eqchi’

Uspanteka

Ixil

Awakateka

Poqomchi’

Chalchiteka

Tekiteko

Sakapulteka

Sipakapense

Achi

K’iche’

Mam

Ch’orti’

Kaqchikel

Poqomam

Tz’utujil

Xinka

itza’

Mopan

Chuj

Garifuna

Q’anjob’al

Popti

Uspanteka

Q’eqchi’

Akateka

Ixil

Awakateka

Poqomchi’

Chalchiteka

Tekiteko

Sakapulteka

Sipakapense

Achi

K’iche’

Mam

Ch’orti’

Kaqchikel

Poqomam

Tz’utujil

Xinka

itza’

Mopan

Chuj

Garifuna

Q’anjob’al

Popti

Akateka

Q’eqchi’

Uspanteka

Ixil

Awakateka

Poqomchi’

Chalchiteka

Tekiteko

Sakapulteka

Sipakapense

Achi

K’iche’

Mam

Ch’orti’

Kaqchikel

Poqomam

Tz’utujil

Xinka

Felipe

Jakelin

Much of the population in the

Western highlands is Indigenous

Claudia

Juan

Carlos

Wilmer

|

While most of Guatemala City’s

3 million people are Ladino, internal

migration from rural Indigneous

communities is common.

Felipe

Jakelin

Much of the population

in the Western highlands

is Indigenous

Claudia

Juan

Carlos

Wilmer

|

While most of Guatemala City’s

3 million people are Ladino, internal

migration from rural Indigneous

communities is common.

Felipe

Jakelin

Much of the population in the

Western highlands is Indigenous

Claudia

Juan

Carlos

Wilmer

|

While most of Guatemala City’s

3 million people are Ladino, internal

migration from rural Indigneous

communities is common.

Water defenders Nery Esteban Pedro and Domingo Esteban Pedro, targeted for resistance to a hydro dam in the Ixquisis microregion

Five members of campesino group CODECA, targeted for resistance to land evictions.

Maya Achi ancestral authority Paulina Cruz Ruiz, targeted for resistance to mining

Ch’orti’ defender Medardo Alonzo Lucero, targeted for resistance to mining

Xinka defender Alejandro Hernández Garcíal,

targeted for resistance to mining

Water defenders Nery Esteban Pedro and Domingo Esteban Pedro, targeted for resistance to a hydro dam in the Ixquisis microregion

Five members of campesino group CODECA, targeted for resistance to land evictions.

Maya Achi ancestral authority Paulina Cruz Ruiz, targeted for resistance to mining

Ch’orti’ defender Medardo Alonzo Lucero, targeted for resistance to mining

Water defenders Nery Esteban Pedro and Domingo Esteban Pedro, targeted for resistance to a hydro dam in the Ixquisis microregion

Five members of campesino group CODECA, targeted for resistance to land evictions.

Maya Achi ancestral authority Paulina Cruz Ruiz, targeted for resistance to mining

Ch’orti’ defender Medardo Alonzo Lucero, targeted for resistance to mining

Xinka defender Alejandro Hernández Garcíal,

targeted for resistance to mining

Massacres Recorded by CEH Per Year

January 1965

“Why do the children of my country leave?…they leave every day for any border that allows them to escape, breathe and leave the miseries in which they were born, in which their parents and grandparents live, who despite working on farms or workshops, in cities or communities have not been able to break the cycle of poverty. They leave because they want to break the curse that snatches from them, when they are born, all their dreams.”

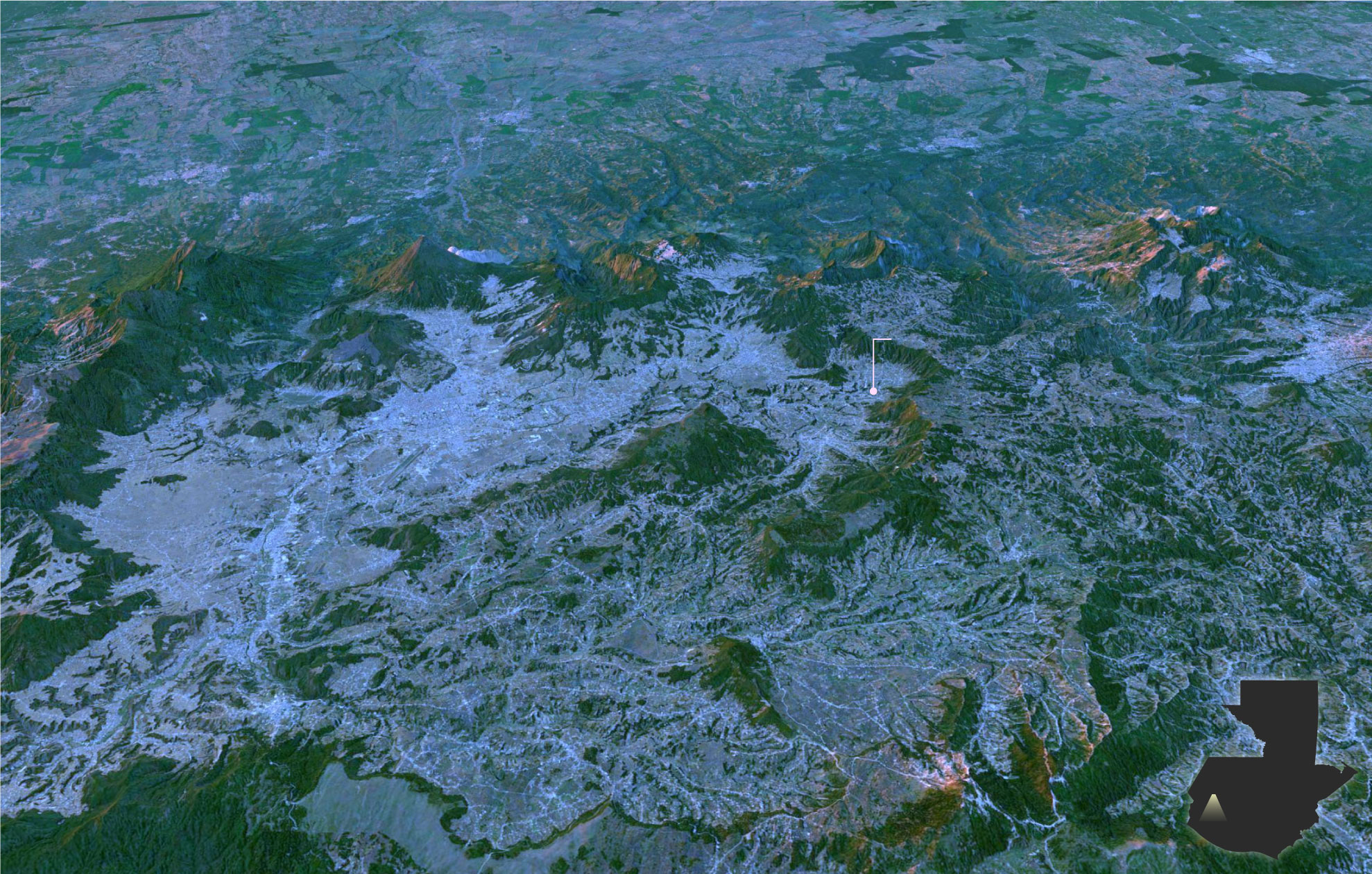

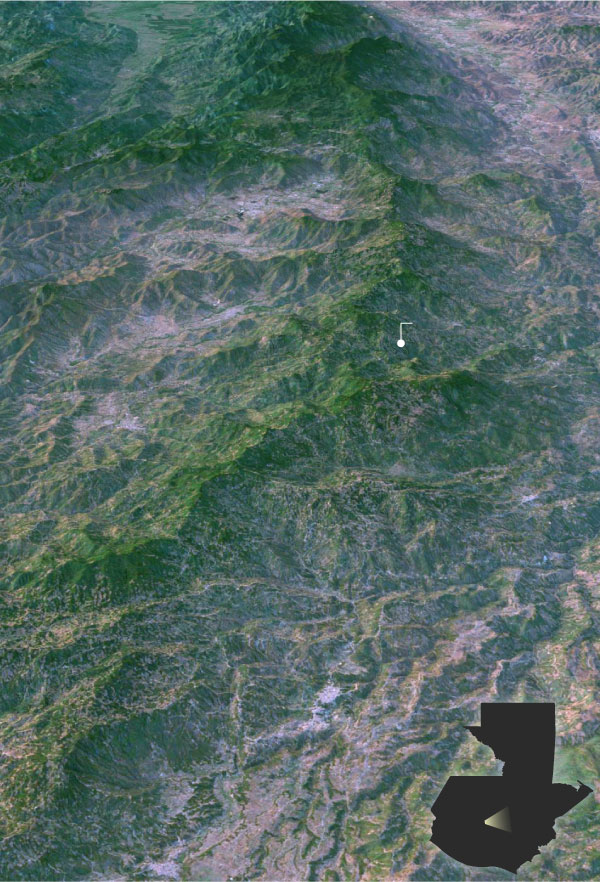

Pacific Lowlands

Volcán Santa María

La Unión

Los Mendoza

San Juan

Ostuncalco

Xela

Western Altiplano

GUATEMALA

Map View

Pacific Lowlands

Volcán

Santa María

La Unión

Los Mendoza

San Juan

Ostuncalco

Xela

Western Altiplano

GUATEMALA

Map View

Pacific Lowlands

Volcán Santa María

La Unión

Los Mendoza

San Juan

Ostuncalco

Xela

Western Altiplano

GUATEMALA

Map View

Claudia Patricia Gómez González grew up in La Unión Los Mendoza, a small town nestled in the western highlands of Guatemala, ancestral territory of the Maya Mam people.

On May 7th, 2018, she left the home she had known all her life.

Photo: PNUD Guatemala/ Fernanda Zelada

Claudia was smart and driven, and had planned to work as an accountant after graduating high school. But every job she applied to required a college degree—something she didn’t have and couldn’t afford.

Photo: Erik Hungerbuhler

Like so many other Indigenous women in her country, Claudia found her opportunities hemmed in by her circumstances. Losing hope of finding a job, she passed her days weaving huipiles to sell in Xela.

Photo: REUTERS/Luis Echeverria

With few options, Claudia came to see migration to the U.S. as her only path forward. “It’s a risk, but I’m wasting away here. I want to be somebody.” she told her parents, according to Marie Claire. “Don’t worry—I will make you very proud of me.” She headed north.

Two weeks later, on May 23rd, 2018, Claudia was shot and killed by a U.S. Border Patrol agent in Rio Bravo, Texas while crossing the border. Her family and community were left devastated and without answers, with the Border Patrol issuing conflicting statements about her death and refusing to name the shooter.

Claudia Patricia Gómez González

Maya Mam | 20 y.o. | 5/23/2018

Jakelin Caal Maquin

Maya Q’eqchi’ | 7 y.o. | 12/8/2018

Felipe Gómez Alonzo

Maya Chuj | 8 y.o. | 12/25/2018

Juan de León Gutiérrez

Maya Ch’orti’ | 16 y.o. | 4/30/2019

Wilmer Josue Ramirez Vasquez

Maya Ch’orti’ | 2 y.o. | 5/16/2019

Carlos Gregorio Hernández Vásquez

Maya Achi | 16 y.o. | 5/20/2019

Claudia’s death was not an isolated tragedy. Over the year following Claudia’s death, five more Indigenous Maya children from Guatemala would lose their lives in U.S. immigration custody, the victims of systemic indifference and militarized borders.

Most news coverage in the U.S. omitted their Indigenous identities, referring to them only as “Guatemalan’. But these six children belonged to five distinct Maya peoples, the Mam, Q’eqchi’, Chuj, Ch’orti’, and Achi, each with distinct languages, territories, and histories. In this map, one dot represents ten people.

In all there are 22 Maya peoples in Guatemala, as well as two non-Maya Indigenous groups, the Xinca and Garifuna. While the government estimates 6.5 million of the country’s 15 million people are Indigenous, this is widely considered to be a significant undercount.

Official census data indicates that about 43% of the population is Indigenous, while the remaining 56% are Ladino, or Spanish-speaking non-Indigenous people. Yet many believe as much as 60% of the population is Indigenous. The uncertainty of the data is symptomatic of the almost complete absence of government services in many rural Indigenous communities.

Photo: Daniele Volpe/New York Times

Despite the steep costs and terrifying risks of the journey north, migration is widespread in many Indigenous areas, a survival strategy in the face of insecurity, abandonment, and climate change. Every year, tens of thousands leave home, driven by structural inequality rooted in centuries of exclusion and exploitation.

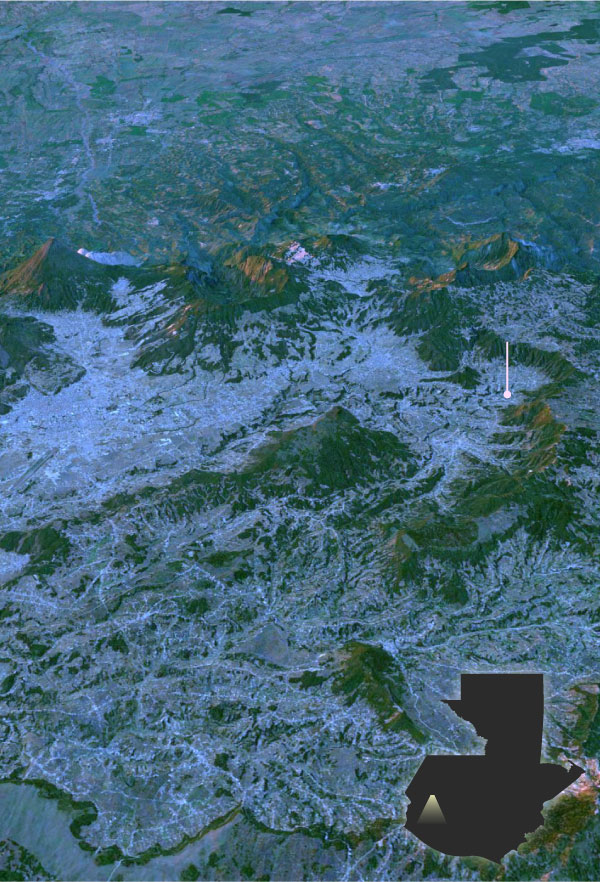

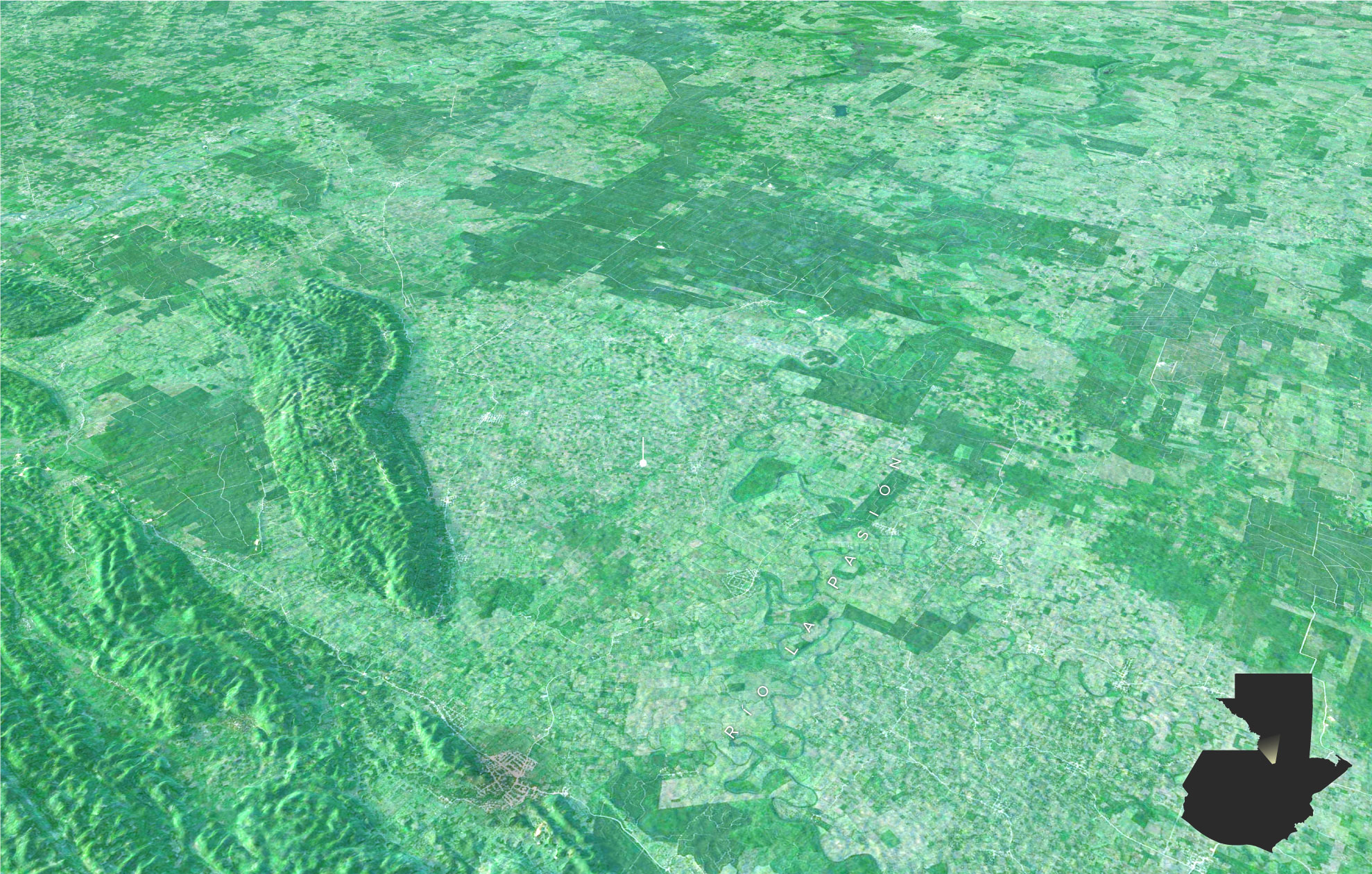

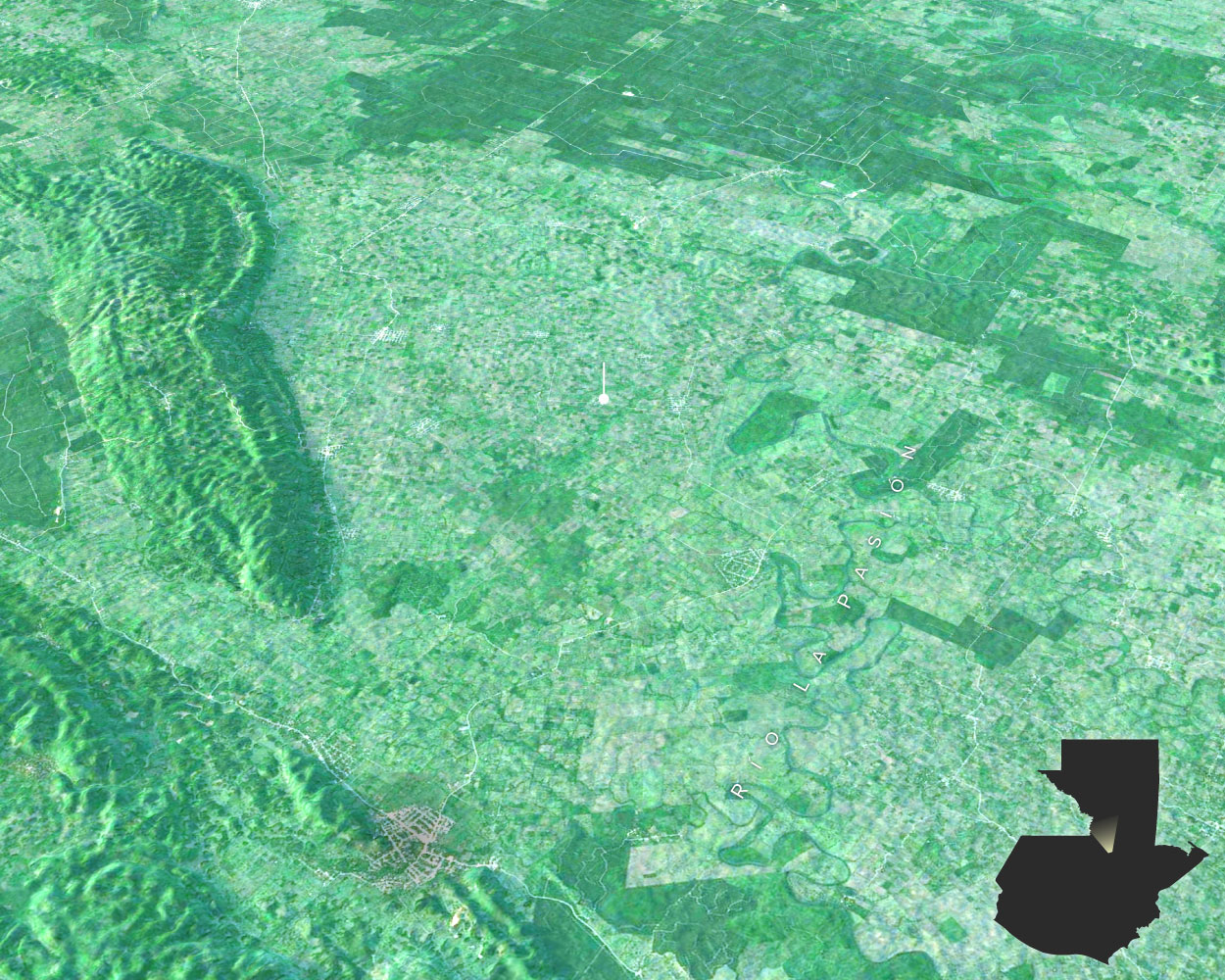

Petén

“Here, there is no opportunity to work, we are receiving low pay for what we produce and everyday things are more expensive...My husband decided to go to the United States to find the means to support our family.”

Sierra

de

Chinajá

San Antonio

Secortez

“[Jakelin’s father] was the one who took the initiative to ask for a pay increase. They accused him of inciting [unrest], and fired him. Those who raise their voices are fired.”

Alta Verapaz

“People go to work on the palm plantations and then begin to consider going to the United States.”

Raxruhá

Map View

GUATEMALA

“Here, there is no opportunity to work, we are receiving low pay for what we produce and everyday things are more expensive...My husband decided to go to the United States to find the means to support our family.”

Petén

“[Jakelin’s father] was the one who took the initiative to ask for a pay increase. They accused him of inciting [unrest], and fired him. Those who raise their voices are fired.”

San Antonio

Secortez

Sierra

de

Chinajá

Alta Verapaz

“People go to work on the palm plantations and then begin to consider going to the United States.”

Raxruhá

Map View

GUATEMALA

Petén

“Here, there is no opportunity to work, we are receiving low pay for what we produce and everyday things are more expensive...My husband decided to go to the United States to find the means to support our family.”

Sierra

de

Chinajá

San Antonio

Secortez

“[Jakelin’s father] was the one who took the initiative to ask for a pay increase. They accused him of inciting [unrest], and fired him. Those who raise their voices are fired.”

Alta Verapaz

“People go to work on the palm plantations and then begin to consider going to the United States.”

Raxruhá

Map View

GUATEMALA

In the Maya Q’eqchi’ region, the voracious expansion of palm oil plantations has left many communities without enough land for traditonal subsistence agriculture. Eight year old Jakelin Caal Maquin headed north with her father from the village of San Antonio Secortez, and died from an untreated bacterial infection in U.S. custody on December 8, 2018.

In the Maya Q’eqchi’ region, the voracious expansion of palm oil plantations has left many communities without enough land for traditonal subsistence agriculture. Eight year old Jakelin Caal Maquin headed north with her father from the village of San Antonio Secortez, and died from an untreated bacterial infection in U.S. custody on December 8, 2018.

For those without sufficient land, working for starvation wages on the palm plantations or migrating north are often the only options. Jakelin’s father Nery was fired from a palm plantation for requesting a pay increase. He was paid only 65 quetzales ($8.50) for a 12 hour workday, less than the legal minimum wage.

"[Because of the violence against activists], people have the same fear now as during the war.”

"We had huge debt and didn’t know how to pay it back. The plan was, if he was to cross, Felipe could go to school and he would work."

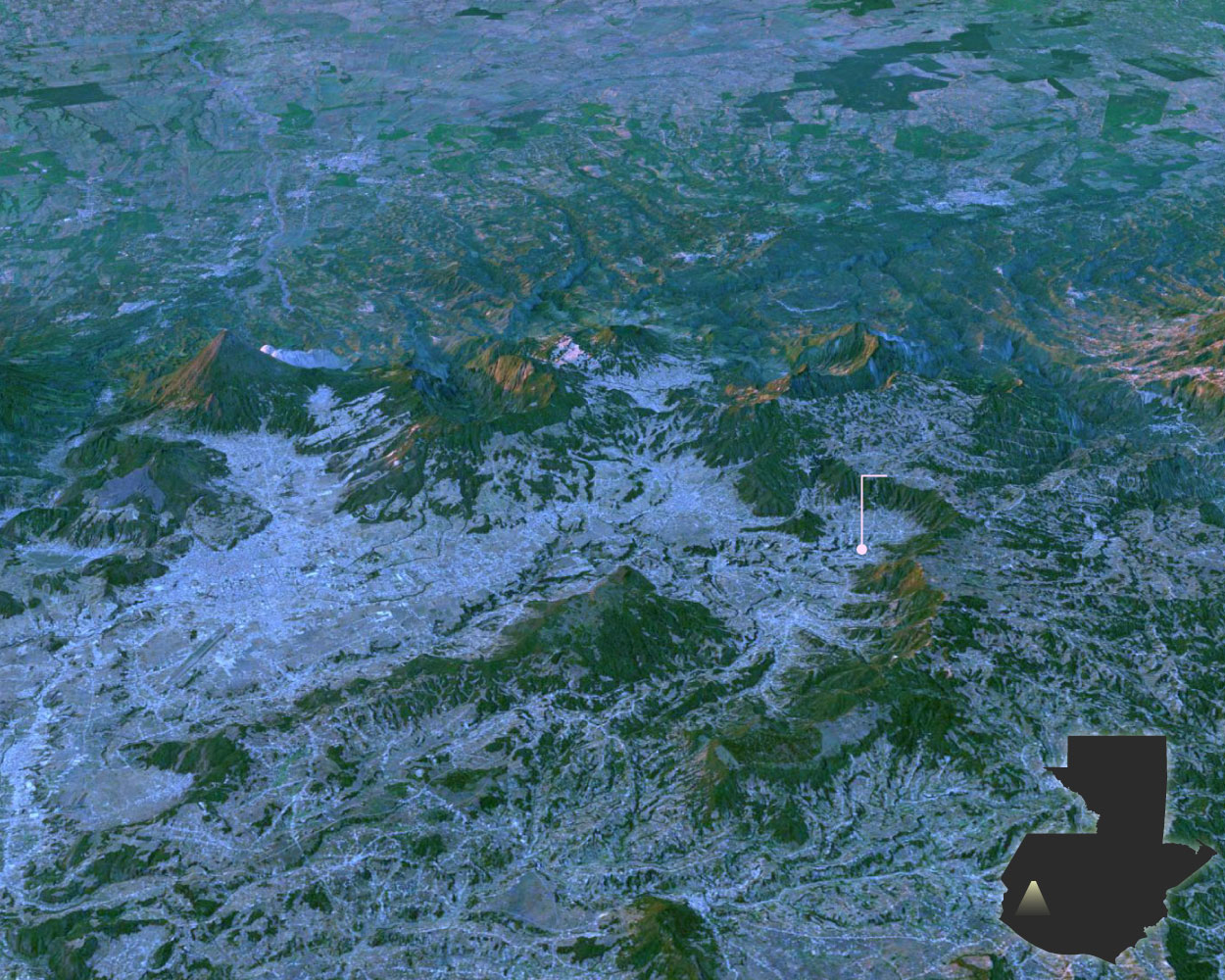

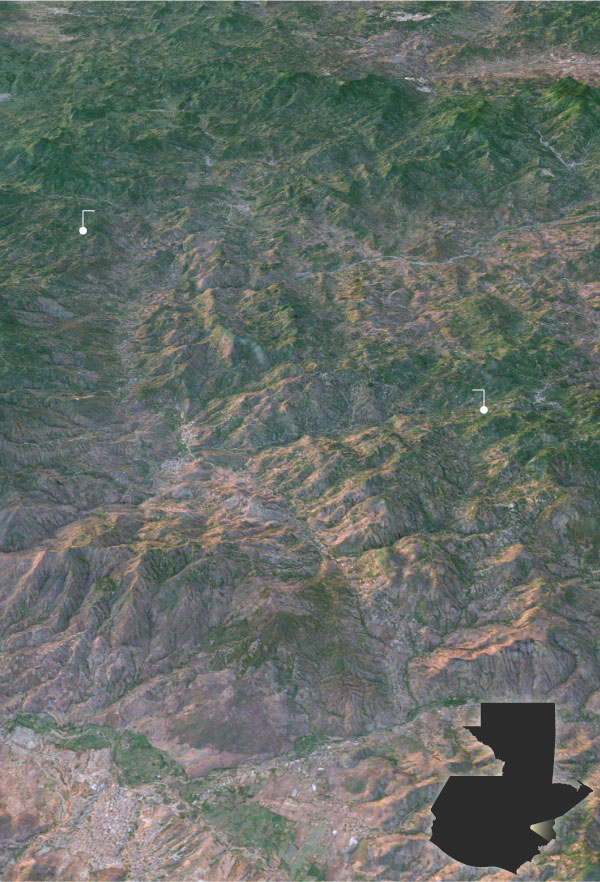

Huehuetenango

Bulej

Yalambojoch

"They speak of development, but what development do they leave behind? They destroyed the land, our forests, and now we see that the development that has been left behind is only destruction, and that we will never return to our nature.”

Community organizer, Ixquisis

Laguna Brava

Map View

GUATEMALA

Chiapas

"[Because of the violence against activists], people have the same fear now as during the war.”

"We had huge debt and didn’t know how to pay it back. The plan was, if he was to cross, Felipe could go to school and he would work."

Huehuetenango

Bulej

Yalambojoch

"They speak of development, but what development do they leave behind? They destroyed the land, our forests, and now we see that the development that has been left behind is only destruction, and that we will never return to our nature.”

Community organizer, Ixquisis

Laguna Brava

Map View

GUATEMALA

Chiapas

"[Because of the violence against activists], people have the same fear now as during the war.”

"We had huge debt and didn’t know how to pay it back. The plan was, if he was to cross, Felipe could go to school and he would work."

Huehuetenango

Bulej

Yalambojoch

"They speak of development, but what development do they leave behind? They destroyed the land, our forests, and now we see that the development that has been left behind is only destruction, and that we will never return to our nature.”

Community organizer, Ixquisis

Laguna Brava

Map View

GUATEMALA

Chiapas

Eight year old Felipe Gómez Alonzo came from Yalambojoch, a small village in the northwestern Maya Chuj region with a history of state violence and displacement. With his family facing crushing debt, Felipe and his father headed for the U.S. hoping to earn money to send home. During the journey, Felipe fell ill and died from influenza in New Mexico on December 25, 2018.

Eight year old Felipe Gómez Alonzo came from Yalambojoch, a small village in the northwestern Maya Chuj region with a history of state violence and displacement. With his family facing crushing debt, Felipe and his father headed for the U.S. hoping to earn money to send home. During the journey, Felipe fell ill and died from influenza in New Mexico on December 25, 2018.

Many of the adults in Yalambojoch spent years as refugees in Mexico during the peak of Guatemala’s armed conflict in the 1980’s, when the US-backed military committed brutal massacres across the region. Today, the criminalization and murder of environmental activists resisting mining and hyrdoelectic projects has resurrected the spectre of the war.

Honduras

El Tesoro

"[Wilmer’s mother] fled the same desperation that [the boy’s father] fled. She fled too, and with a sick child. There was nothing else they could do."

“Now not one [crop] survives. Now we cannot do anything. This drought does not end.”

Tituque

Olopa

Esquipulas

Camotán

“The main cause of food insecurity is due to the lack of public policies that protect and promote the capacity and ways in which families feed themselves.”

Chiquimula

GUATEMALA

Chiquimula

Map View

“Now not one [crop] survives. Now we cannot do anything. This drought does not end.”

Honduras

El Tesoro

"[Wilmer’s mother] fled the same desperation that [the boy’s father] fled. She fled too, and with a sick child. There was nothing else they could do."

Tituque

Olopa

Camotán

Chiquimula

“The main cause of food insecurity is due to the lack of public policies that protect and promote the capacity and ways in which families feed themselves.”

Chiquimula

GUATEMALA

Map View

Honduras

El Tesoro

"[Wilmer’s mother] fled the same desperation that [the boy’s father] fled. She fled too, and with a sick child. There was nothing else they could do."

“Now not one [crop] survives. Now we cannot do anything. This drought does not end.”

Tituque

Olopa

Esquipulas

Camotán

“The main cause of food insecurity is due to the lack of public policies that protect and promote the capacity and ways in which families feed themselves.”

Chiquimula

GUATEMALA

Chiquimula

Map View

The eastern Maya Ch’orti’ region lies squarely in the Dry Corridor, a swath of Central America where extreme weather linked to climate change has made subsistence farming increasingly untenable. Sixteen year old Juan de León Gutiérrez left the village of El Tesoro in the face of relentless drought in April 2019, and died from an untreated sinus infection in an El Paso detention center.

The eastern Maya Ch’orti’ region lies squarely in the Dry Corridor, a swath of Central America where extreme weather linked to climate change has made subsistence farming increasingly untenable. Sixteen year old Juan de León Gutiérrez left the village of El Tesoro in the face of relentless drought in April 2019, and died from an untreated sinus infection in an El Paso detention center.

Just a few weeks later, 2 year old Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, from the Ch’orti’ village of Tituque, died from pneumonia in El Paso. Like many from the region, Wilmer was chronically malnourished, and his family had no money for health care. When he fell ill, his mother took him north in desperation.

Just a few weeks later, 2 year old Wilmer Josué Ramírez Vásquez, from the Ch’orti’ village of Tituque, died from pneumonia in El Paso. Like many from the region, Wilmer was chronically malnourished, and his family had no money for health care. When he fell ill, his mother took him north in desperation.

The political and social exclusion of Indigenous communities has led to staggering rates of food insecurity. According to UNICEF, the rate of chronic malnutrition for Indigenous children in Guatemala is as high as 80%. With scant support from the government, many families risk the dangerous journey north as a last resort.

"Here in Guatemala, the governments have dedicated themselves to corruption, and they have forgotten the people, all of us who live in the high plains of the country. This is why so many people make the trip. They immigrate because there is no work.”

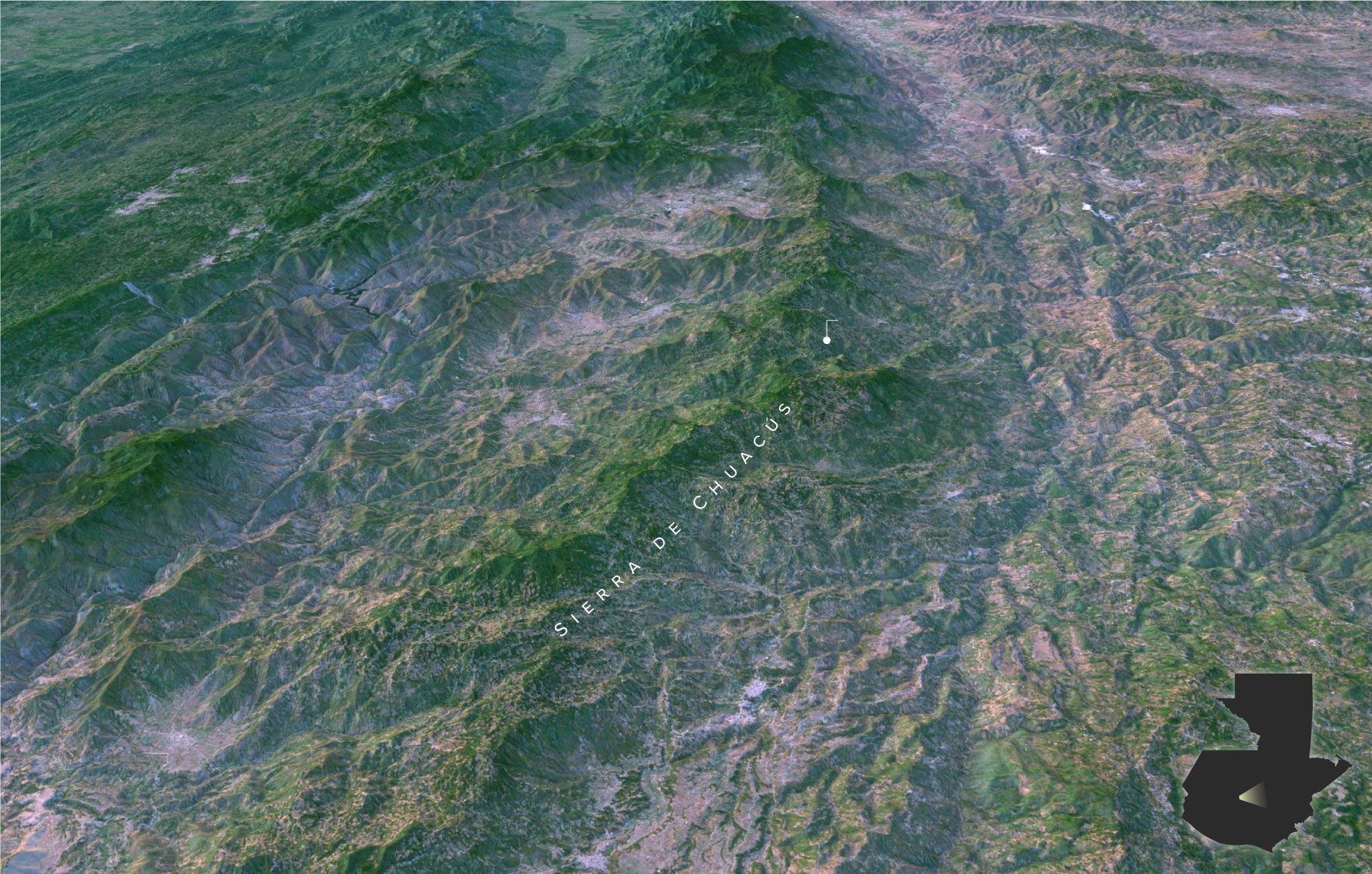

Rabinal

Río Negro

Cubulco

San José El Rodeo

"It feels like we are returning to the 1980s...[corruption] is the cause of much of the poverty and violence. There have been no projects completed in our community.”

—Miguel Angel Manuel Alvarado,

Achí Mayan Ancestral Authority of Rabinal

Baja Verapaz

"I am here with that pain [of losing Carlos]. It sort of breaks the mind to be thinking about it so much.”

GUATEMALA

Map View

"Here in Guatemala, the governments have dedicated themselves to corruption, and they have forgotten the people, all of us who live in the high plains of the country. This is why so many people make the trip. They immigrate because there is no work.”

Rabinal

Cubulco

San José El Rodeo

"I am here with that pain [of losing Carlos]. It sort of breaks the mind to be thinking about it so much.”

Baja Verapaz

"It feels like we are returning to the 1980s...[corruption] is the cause of much of the poverty and violence. There have been no projects completed in our community.”

—Miguel Angel Manuel Alvarado,

Achí Mayan Ancestral Authority of Rabinal

GUATEMALA

Map

View

"Here in Guatemala, the governments have dedicated themselves to corruption, and they have forgotten the people, all of us who live in the high plains of the country. This is why so many people make the trip. They immigrate because there is no work.”

Rabinal

Río Negro

Cubulco

San José El Rodeo

"It feels like we are returning to the 1980s...[corruption] is the cause of much of the poverty and violence. There have been no projects completed in our community.”

—Miguel Angel Manuel Alvarado,

Achí Mayan Ancestral Authority of Rabinal

Baja Verapaz

"I am here with that pain [of losing Carlos]. It sort of breaks the mind to be thinking about it so much.”

GUATEMALA

Map View

In the Maya Achi region north of the capital, unequal access to land and opportunities has driven many to migrate. Carlos Gregorio Hernández Vásquez, a 16 year old Maya Achi, left his hometown of San Jose El Rodeo in May 2019 to support his family, but died from influenza in a Border Patrol holding cell where he was abandoned without receiving medical attention.

In the Maya Achi region north of the capital, unequal access to land and opportunities has driven many to migrate. Carlos Gregorio Hernández Vásquez, a 16 year old Maya Achi, left his hometown of San Jose El Rodeo in May 2019 to support his family, but died from influenza in a Border Patrol holding cell where he was abandoned without receiving medical attention.

The genocidal violence of the 1980’s left lasting scars here, destroying community organizations and displacing Achi people from their lands. Today, neoliberal economic development is leaving similar corrosive effects, destroying rivers and forests without benefiting the local communities.

Indigenous youth in Guatemala are faced with an impossible dilemma.

Those who stay and struggle for a dignified life at home face stacked odds in a country characterized by dystopian levels of inequality. A 2015 study by research firm WealthX estimated that Guatemala’s richest 260 people have a combined wealth of US$30 billion, while most people survive on less than $3 per day. Two thirds of arable land is owned by just 2% of landowners, most dedicated to large-scale exports like palm oil, sugar cane, and bananas.

On the other hand, migration means a traumatic separation from family and culture, and is increasingly risky. The U.S.’s militarized immigration enforcement strategy is designed to kill migrants, and it is working. Every year hundreds die crossing the desert and thousands more disappear in Mexico. Those who reach the U.S. suffer abuses in the workplace and live in constant fear of deportation.

Photo: Rosendo Castillo Azurdia

Undeterred by the risks, some 20% of the population in many Indigenous villages has emigrated north, a testament to the severity and intransigence of structural racism in Guatemala. Despite sustained protest by Indigenous and working class movements, power and wealth remain concentrated in the hands of the corrupt economic elite, who control the government and allow transnational corporations to operate with impunity.

Photo: Fabio Erdos/ActionAid

Ironically, U.S. foreign policy has played a key role in maintaining these uneven power relations and producing the very “root causes” of migration it claims to work towards solving today. Far from a beacon of hope, the U.S. has long been an architect of suffering for Indigenous Guatemalans, who continue to survive and resist after more than 500 years of cyclical invasion and exploitation.

“From the time when Alta Verapaz was populated by only the brave Q’eqchi’ race until this moment…from the exploitation of the conquistador’s whip to the infamous exploitation of the plantation owners…they have taken your property, your liberties, your rights…Alta Verapaz workers are the most exploited in all the country. The struggle of the reactionaries, of these ‘friends of order’ who scowl at us on the street, is to impose this regime on the whole republic. We, in contrast, want to destroy this system. It is not only agrarian reform that will resolve the problem. We need to treat Indians justly…with respect like human beings. We promise you better houses and a better salary. We promise you a little more justice.”

—Jacobo Arbenz, campaign speech in Cobán, Alta Verapaz, 1950

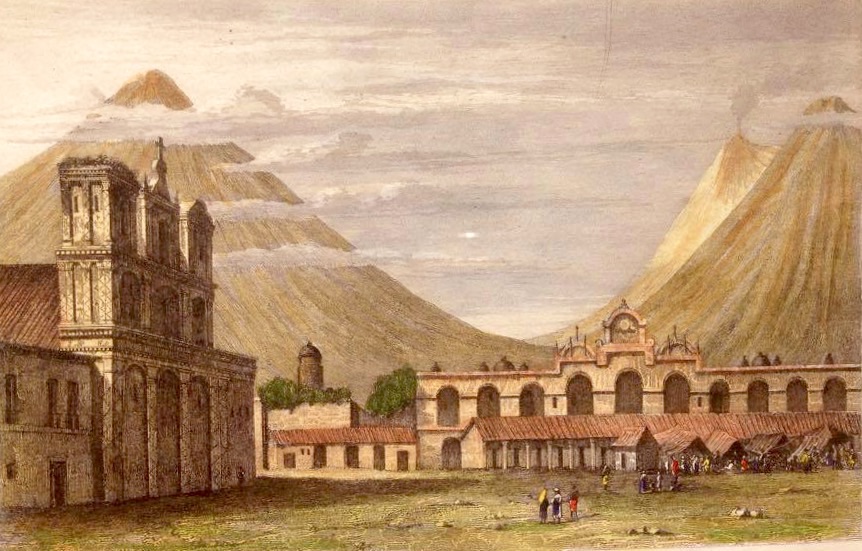

Illustration: Frederick Catherwood

The colonial logic of extraction and cruelty that persists today in Guatemala began in the days of the Spanish invasion, when roughly two-thirds of the Maya population died in the conquest and subsequent epidemics. The Spanish claimed vast tracts of land and instituted a brutal system of forced labor, justifying their violence with a racist ideology of criollo superiority.

Photo: Adam Jones

Maya peoples resisted fiercely, preserving autonomy and communal land holdings in some highland regions. Still, by the end of the colonial period, persistent patterns of exploitation were established in Guatemala: mono-export, weak government and a lack of infrastructure, and the channeling of wealth to a tiny oligarchy and foreigners.

Photo: Byron Garoz

For Indigenous peoples, independence from Spain in 1821 brought no change for the better. In the words of thousands protesting during observation of the bicentennial in 2021, there was “nada que celebrar”, or “nothing to celebrate”. Dispossession and the concentration of wealth in the hands of the tiny elite only accelerated in the ensuing decades with the growth of the plantation economy.

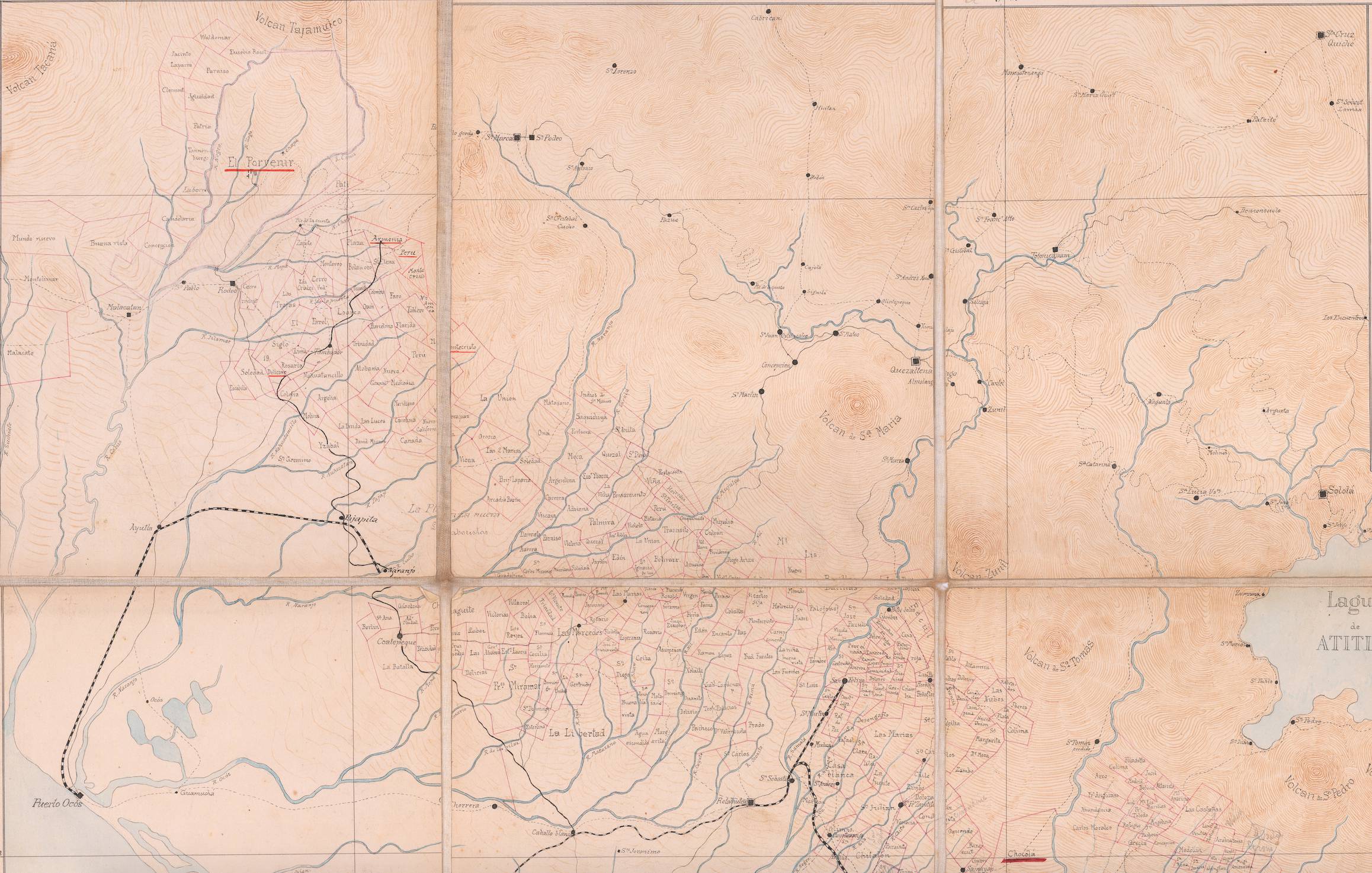

As the craze for coffee and sugar accelerated in the late 1800’s, so did the expropriation of lands from Indigenous communities. In the Mam highlands, communal land holdings were decimated and forced labor on plantations was widespread. This 1888 map by Carlos Schulitz shows the massive scale of the coffee economy in the altiplano, where almost all land suitable for coffee was carved up into plantations.

During the first half of the 20th century, the Guatemalan government granted massive concessions to foreign capital, especially to U.S. companies. Dictators Manuel Estrada Cabrera(1898-1920) and Jorge Ubico(1931-1944) ceded so many monopolies and priveleges that by 1944, “United States companies virtually dictated Guatemala’s economic life”.

Photo: Baker Library Historical Collections. Harvard Business School.

First and foremost among the U.S. corporations was United Fruit Company (UFCo), which monopolized banana production, controlled the railroads and ports, and owned much of the country’s best land. By the middle of the 20th century, UFCo owned 42% of Guatemala’s land and posted annual profits of more than $65 million, more than twice the revenue of the Guatemalan government.

Photo: Hemeroteca Nacional de Guatemala, Prensa Libre

The repression of the plantation era peaked with the 14-year reign of Ubico, who maintained control with thousands of secret police who routinely murdered and tortured dissidents. Ubico instituted a brutal system of forced labor that ensured UFCo and the coffee plantations a steady supply of cheap labor despite severe, underpaid working conditions.

Finally, in 1944, a student strike snowballed into a popular revolution that toppled Ubico and began what some historians have called the ‘Democratic Spring’. For the next ten years, a fragile representative democracy held sway and the feudal domination of the planters and foreign companies was truly challenged for the first time.

President Juan José Arévalo (1945-1951) abolished forced labor, enabled basic freedoms of speech and press, and passed a labor code that enabled union organizing. Yet Arévalo’s government limited rural labor unions and failed to truly challenge the foreign monopolies. President Jacobo Árbenz (1951-1954) confronted the landed oligarchy and corporations more aggressively, most notably through the agrarian reform of 1952.

Photo: Sebastian Oliva

The 1952 Agrarian Reform Law was designed to address the most important and enduring barrier to equality in Guatemala: access to land. The law enabled the expropriation of fallow land from the largest landowners and its distribution to landless citizens. The law was supported by the majority of Indigenous and working class people, and bitterly resisted by the tiny elite, who saw it as an existential threat.

No landowner stood to lose more than UFCo, which had only 15% of its sprawling 550,000 acres in active production. From the earliest days of the 1944 revolution, UFCo and the landed elite had resented its democratic reforms and plotted its overthrow. UFCo, connected at the highest levels of the Eisenhower administration, finally convinced the U.S. government to topple the Arbenz government in 1954.

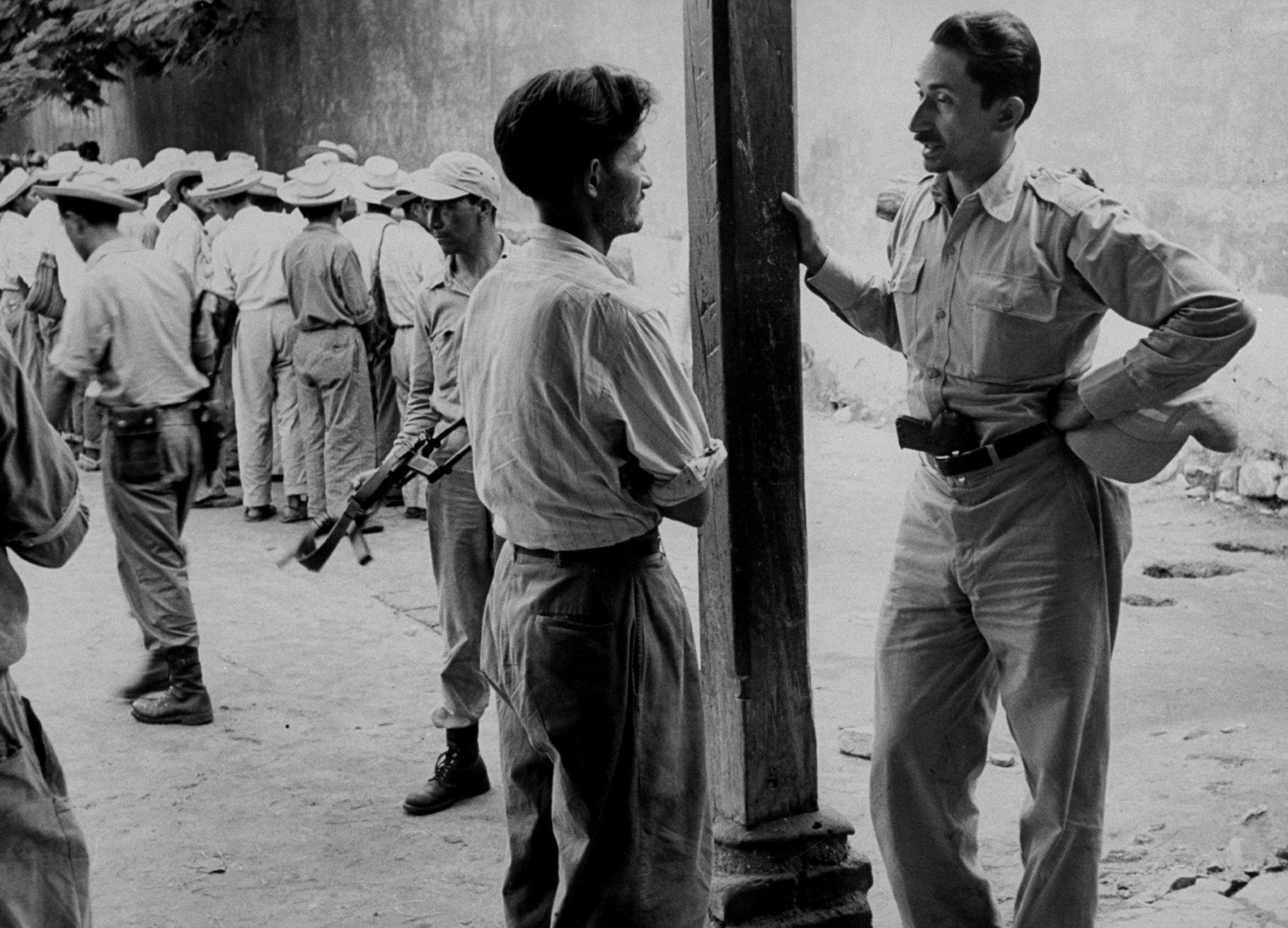

Photo: George Silk/The LIFE Picture Collection

While the Eisenhower administration publically claimed a Communist threat as pretext for the CIA coup, the real aim was to oust Arbenz in favor of a repressive government that would protect the profits of the U.S. monopolies. According to historians, “every U.S. policymaking official involved in the decision to overthrow the Guatemalan government, except for President Eisenhower himself, had a family or business connection to United Fruit Company”.

Photo: CriticalPast

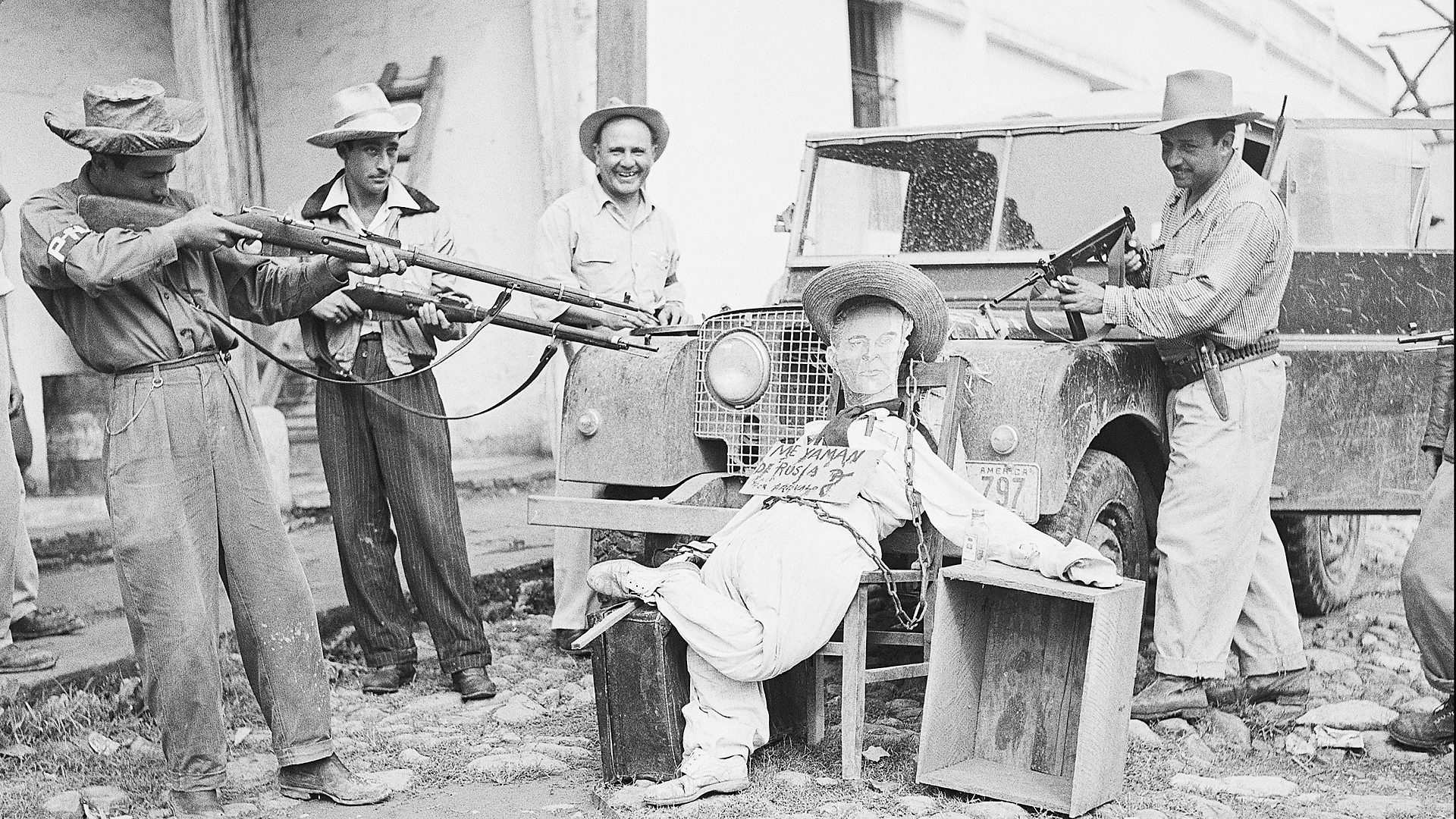

The CIA used a mercenary army, aerial bombing, and a barrage of psychological warfare to overthrow Arbenz and install Carlos Castillo Armas in his place. In the months following the coup, the U.S. government warmly embraced Armas as he presided over a bloody counter-revolution that saw thousands of unionists, campesinos, and civil society leaders brutally murdered and imprisoned.

Photo: Bettmann, Getty Images

An estimated three to five thousand people were murdered. At UFCo’s Finca Jocotán on the south coast, upwards of 1,000 union organizers were rounded up and executed. Campesinos who had participated in the agrarian reform were mercilessly repressed. According to one Ch’orti’ survivor, “When Jacobo Arbenz left there was a great slaughter. Corpses appeared on the roads. In the time of Castillo Armas, the Army went everywhere killing peasants.”

Photo: Lianne Milton

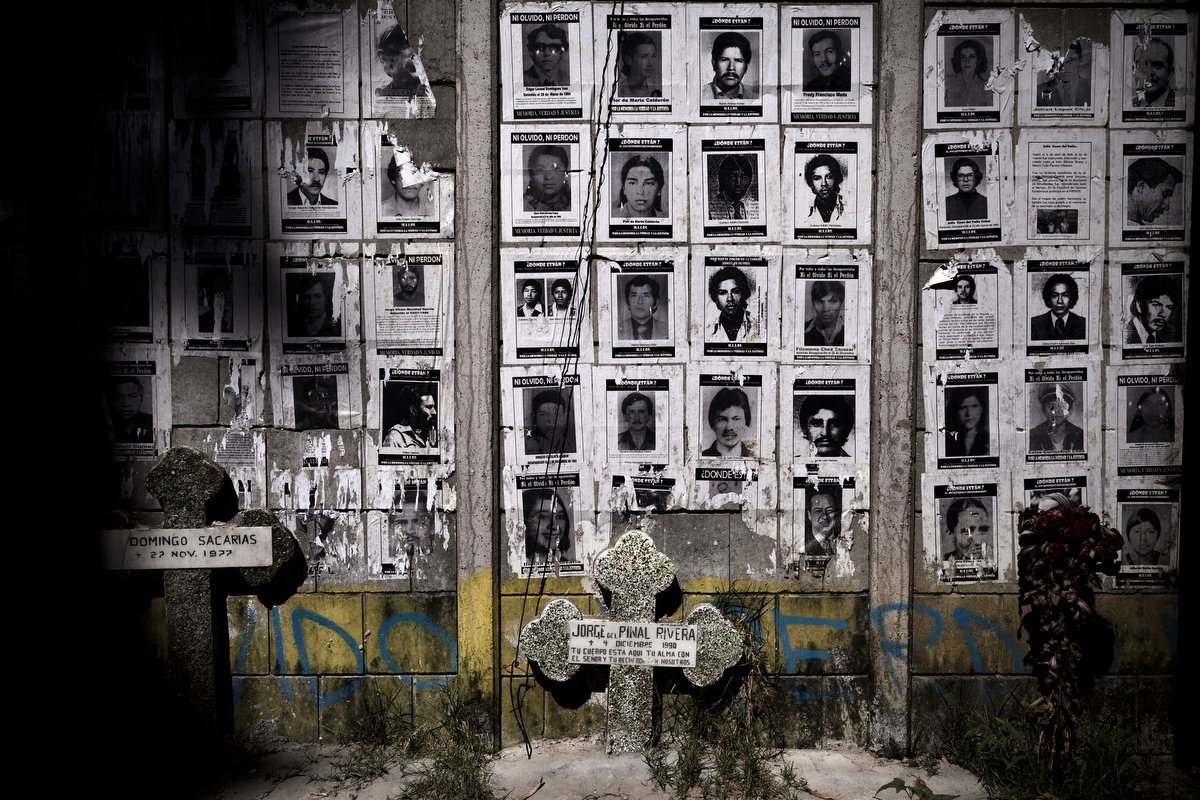

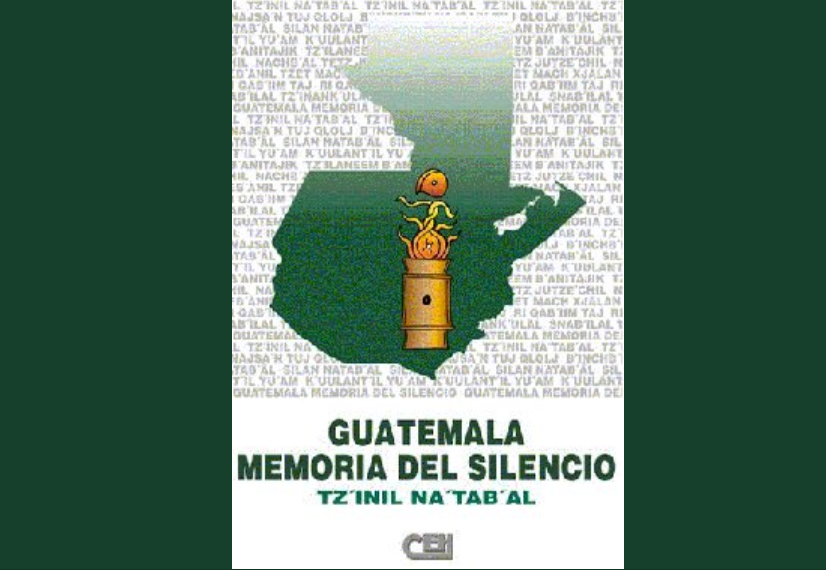

The 1954 coup kicked off a spiral of violence that would lead to four decades of repression and terror. With democratic progress stifled, guerrilla movements sprang up, and a series of brutal military governments waged war against its own citizens. An estimated 200,000 people were killed and disappeared, and more than 1.5 million displaced during the conflict, according to a U.N.-sponsored truth commission called the Historical Clarification Committee (CEH).

The CEH’s 4,000+ page report, based on the testimony of survivors, recorded thousands of human rights violations and concluded that 93% were committed by the government forces. These included more than 600 massacres, formally defined by the CEH as “the arbitrary execution of more than five people, carried out in the same place and as part of the same operation, when the victims were in a state of absolute or relative defenselessness.”

The massacres overwhelmingly targeted Indigenous communities. Most included not just the mass killing of defenseless people, but heinous acts including torture, sexual violence, and the burning of entire villages.

To visualize how this indiscriminate violence left lasting devastation in Indigenous communities, including the home regions of Claudia, Jakelin, Felipe, Juan, Wilmer, and Carlos, I transcribed data on the 600+ massacres recorded in the CEH report and mapped them.

Ch’orti’ Region 1965-1970

The Ch’orti’ region suffered some of the first massacres recorded by the CEH in the conflict period (1960–1996). During the mid 1960’s, the Guatemalan army and CIA-trained death squads killed thousands of peasants in the eastern part of the country.

Though the guerrilla combatants in the east numbered less than 500, the military counter-insurgency claimed an estimated 6,000-8,000 lives, as the army executed suspected leftists with impunity. While the massacres recorded by the CEH represent only a fraction of the death toll, the testimony of survivors reveals the devastation wrought by the "counter-terror" campaign.

Declassified documents show that the U.S. government was fully aware of ongoing human rights violations. In March of 1968, a State Department official wrote the following in a memo to Washington:

“The counter-terror is indiscriminate…The official squads are guilty of atrocities. Interrogations are brutal, torture is used and bodies are mutilated…We have been so obsessed with the fear of insurgency that we have rationalized away our qualms and uneasiness. This is not only because we have concluded we cannot do anything about it, for we never really tried. Rather we suspected that maybe it is a good tactic, and that as long as Communists are being killed it is alright…we will stand before history unable to answer the accusations that we encouraged the Guatemalan Army to do these things.”

Q’eqchi’ Region 1970-1978

Across Guatemala, state violence was used to crush any resistance to the domination of the elites and foreign corporations. In Q’eqchi’ territory, peaceful resistance to land dispossession and mining projects was treated as Communist insurgency and met with indiscriminate violence.

On May 29, 1978, the Army opened fire on a crowd of Q’eqchi’ peasants gathered in Panzós to protest land evictions and intimidation by the local planter elite. At least 50 were massacred, and over the next four years the army executed more than 300 ancestral authorities and community organizers involved with the land dispute.

With grassroots resistance to the exploitation of Indigenous lands stifled, foreign investments ballooned as U.S. corporations worked in tandem with the repressive elite to expand their operations. The Bank of America’s clients included Guatemalan President Fernando Romeo Lucas García (1978-1982), and its investment portfolio "[read] like a "Who’s Who" of human rights violators”.

Achi Region 1978-1982

The violence continued to escalate after Panzós. According to the CEH, the early 1980’s were the years "most stained with death, destruction and pain in the contemporary history of the country.". Genocide was unleashed in several Indigenous territories, including that of the Maya-Achi, where the Army savagely repressed villagers who resisted the construction of a hydroelectic dam financed by the World Bank.

Achi people from the village of Río Negro refused to abandon their ancestral lands, protesting the dam that was slated to flood more than 50 square kilometers, displace thousands, and destroy at least 50 ceremonial and archeological sites. The villagers were branded guerrillas, ruthlessly massacred, and driven into the mountains where many perished from starvation. Months after the massacres, the reservoir was filled.

Chuj Region 1982

Genocide also devastated northern Huehuetenango in 1982, where the Chuj and Q’anjob’al peoples were "perceived not only as rebellious or different from the ladino group, but also antagonistic to authority and especially capable of organizing to achieve their interests." The communities’ defense of their forests against incursions from a logging company were among the factors that led to the Army classifying the Chuj people as an internal enemies.

The scorched earth campaign conducted by the Army targeted entire communities for destruction, and shocking atrocities such as the San Francisco massacre prompted 80% of the population to flee. Most of the communities were left abandoned, and many people fled to Mexico where they survived in refugee camps for years.

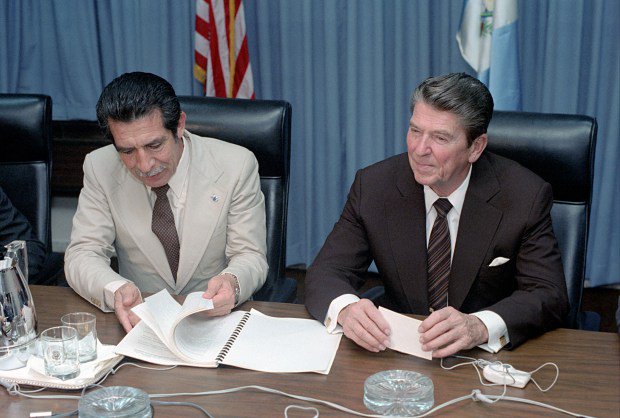

The U.S. continued to support the government’s criminal counter-insurgency campaign with money, weapons, and diplomatic support. On December 4, 1982, U.S. President Ronald Reagan met with Guatemalan dictator Efraín Ríos Montt, who would later be convicted of genocide, and stated, “I know that President Rios Montt is a man of great personal integrity and commitment…I know he wants to improve the quality of life for all Guatemalans and to promote social justice”.

Massacres and human rights violations continued to devastate Indigenous communities across Guatemala through the 1980’s and 1990’s. By the official end of the internal armed conflict in 1996, an estimated 200,000 people were dead or disappeared, 1.5 million displaced, and incalculable damage was done to social movements and democratic progress in Guatemala.

The majority of the victims were civilians. The CEH report concluded that “at no time during the internal armed confrontation did the guerrilla groups have the military potential necessary to pose an imminent threat to the State…the State deliberately magnified the military threat of the insurgency". The excesses of government terror were felt most keenly in Indigenous communities, where massacres and executions "were not only an attempt to destroy the social base of the guerrillas, but above all, to destroy the cultural values that ensured cohesion and collective action in Mayan communities. "

The CEH’s landmark report was only made possible by the dedication and bravery of the witnesses and organizers, who fought for justice despite great personal peril. Many of the recruiters and interviewers belonged to popular movement organizations such as the AEU (San Carlos Student Association), GAM (Mutual Aid Group), CUC (Committee for Peasant Unity), and CONAVIGUA (National Association of Guatemalan Widows), human rights groups whose members were criminalized and murdered during the conflict.

Photo: UN Women/Ryan Brown

Despite heroic efforts to expose state-sponsored violence, the publication of the truth commision’s report did not signal a new age of accountability and justice in Guatemala. Impunity was built into the CEH from the start, as it was bound by its creation to avoid naming individual perpetrators. The recommendations of the CEH, like the broader commitments of the Peace Accords, were never really implemented, and prosecution of war criminals has been delayed and obstructed at every turn.

Photo: Daniele Volpe/ICRC

From the devastation of the colonial invasion, to the exploitation of the plantation era, to the genocidal violence of the armed conflict, a history of invasion has left deep scars in Indigenous communities. The structural inequality that drives the migration of Maya children like Claudia, Jakelin, Felipe, Juan, Wilmer, and Carlos is inextricably linked to this history—especially since the cycle of invasion has continued in the post-war era.

“What we are facing today is not so different from what happened before, and instead is the continuation of a policy designed to appropriate our natural resources….When the Peace Accords were signed, an underlying objective was to benefit big business, transnational corporations, mega-projects, and the global economy. It was in the interest of global and transnational capital to end the war and to clean up our lands in order to implement their projects. Of course, it wasn’t explained this way. The existence of an economic agenda was hidden.”

—Rigoberto Juárez Mateo, Maya Q’anjob’al ancestral authority

Photo: Anna Fawcus/Oxfam America

Democracy and dignity have remained under attack in Guatemala’s post-war period. The 1996 Peace Accords promised to address socioeconomic disparities, protect human rights, and create a multicultural state with equal rights for Indigenous peoples. Instead, the peace process paved the way for a new stage of invasion marked by the intensification of extractive capitalism, the empty promises of neoliberal multiculturalism, and the violent repression of land, water, and human rights defenders.

Photo: Teixchel

The rhetoric of multiculturalism promoted by the state has proven hollow. According to Kaqchiquel anthropologist Rigoberto Ajcalón Choy, “the Guatemalan state began to tolerate certain indigenous claims, especially to cultural rights, but it was unwilling to accept their economic rights, particularly those related to the struggle for territory and resources-oil, water, forests, minerals, plants, and animals, among others- because these affect dominant-sector interests and interfere with the government’s plan to promote capitalist investments”.

Photo: Ralph Alswang

While the Guatemalan government paid lip service to Indigenous rights, a wave of neoliberal economic reforms in the 1990’s and early 2000’s ensured the continued domination of the elite and transnational corporations. These reforms included the privatization of public services, the passage of mining laws biased towards the interests of foreign capital, and the passage of the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) in 2005.

Photo: Moises Castillo/Associated Press

When U.S. President Bill Clinton visited Guatemala in March of 1999, just weeks after the release of the CEH report, he broke with previous policy by admitting and apologizing for the role of the U.S. in the human rights abuses of the war. Clinton promised to “support the peace and reconciliation process in Guatemala”, a promise contradicted in the ensuing years by the maintenance of close ties with the corrupt elite, the promotion of a development agenda that prioritizes corporate profits over human rights, and the escalation of a destructive policy of border militarization.

Photo: Sarah L. Voisin/The Washington Post

In 2005, a U.S. Congressman lauded CAFTA as the “the best immigration, anti-gang, and anti-drug policy at our disposal”, claiming like other advocates that the agreement would materially improve the lives of Guatemalans, reduce violence, and empower workers. Instead, CAFTA flooded Central America with cheap U.S. agricultural exports, displacing millions of rural workers who couldn’t compete against subsidized agro-business. Nor did conditions for workers improve. In 2018, the International Trade Union Confederation labeled Guatemala “one of the worst violations of workers’ rights, with widespread and systemic violence against workers and trade unionists”.

Today’s targeted repression against environmental defenders and activists bears a striking resemblance to the abuses of the past. From 2018 to 2020, a Guatemalan NGO dedicated to tracking violence against activists documented 57 murders, many in Maya communities that suffered massacres during the war (UDEFEGUA). Hundreds more were the targets of threats, intimidation, and criminalization by corporate and state actors.

Photo: EntreMundos

Abandoned by the government, struggling to make ends meet, and facing retaliation for resistance, many choose to migrate in search of dignity and security abroad. But many also choose to stay, continuing a tradition of resistance and survival, refusing to be separated from their lands, raising their voices and organizing to demand change.

Photo: Carlos Sebastián/Nomada

Near Felipe Gómez Alonzo’s village of Yalambojoch, the Peaceful Resistance of the Microregion of Ixquisis continue to defend their territory from the unlawful development of a hydroelectric dam. They are one of many Indigenous communities across Guatemala demanding that the government honor their right to “prior, free, and informed consent” as guaranteed by law, and halt extractive mega-projects that destroy the land and leave communities impoverished.

Photo: Secretaría de Cultura Ciudad de México

Organizing in the streets and advocating change through art, Guatemalans continue to demand an end to discrimination against Indigenous peoples, women, and the poor. Leaders like Kaqchikel singer Sara Curruchich exemplify the resolve of Indigenous women, who she says should be considered “actors of change, fundamental actors for the prevalence of our Indigenous knowledge, and a pillar of sustainability for our communities and for the entire country, for the world”.

Photo: Duncan Cumming

Transnational advocacy networks continue to struggle against border militarization and the criminalization of migrants, which compound insecurity and result in the death and disappearance of thousands each year. Groups including the Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants are drawing attention to the cruelty of immigration enforcement regimes, while others such as the ACLU are demanding justice for the deaths of Claudia and other migrant youth.

Photo: Rosa M. Tristán/ Caal Xol family

Despite criminalization, communities continue to defend their lands and denounce the corruption of the state and economic elite, whose power is visible in institutions such as the CACIF, a coalition of business elites that “essentially exerts a veto power on undesirable economic policies”. Led by defenders like Q’eqchi’ schoolteacher Bernardo Caal Xol, recently released after four years of imprisonment for environmental defense, the people continue to struggle against extractivism, impunity, and structural racism.

The mass exodus that claimed the lives of Claudia, Jakelin, Felipe, Juan, Wilmer, and Carlos will end only when their voices are heard. Until then, the people will continue to fight, in memory of those who came before, and on behalf of those to come, for the right to dignified life in Guatemala. ♦